The Open Where Not To See

An exhibition of photographs exploring the opening up and changing of how we see (and don’t see) ourselves, relate to others, and experience reality. The alternative process photographs act as a fragmented window into constructs of meaning—panes of glass floating in the intersecting planes of philosophy, theology, and art. The exhibition is a parallel discourse to the written component of my artist’s master’s thesis that explores points of confluence and tension between western philosophy, postmodern thought, and diverging biblical/theological voices. Come and (not) see.

Below are a series of text fragments that informed my creating of the pieces. If you would like to read the entire work, simply drop me a note in the comments and I am happy to send you the full text document. The hard copy is also available at the Luther Seminary Library (http://luthersem.worldcat.org/title/open-where-not-to-\see/oclc/881729595&referer=brief_results).

Emilie Bouvier

Titles: Structuralism, The Other, An Opening, Installation Detail 1, Mise en Abime (Installation Piece). Face to Face: Fragment 1-5, Installation Detail 2-5

Photographs made printing from film onto glass plates using liquid emulsion as well as using traditional film to photo paper

2014

The Open Where Not To See

Text Fragments

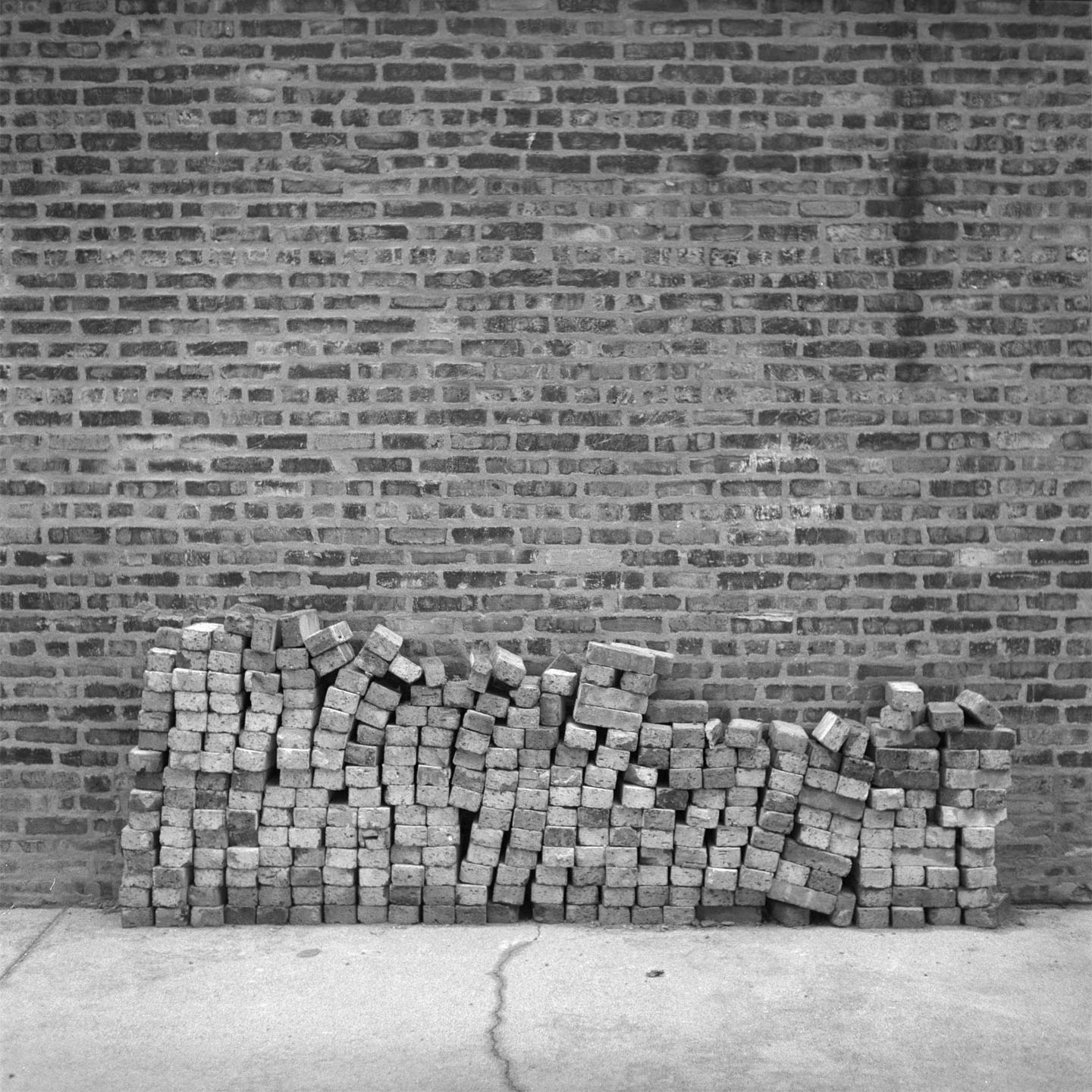

Structuralism

To lay brick you must be initiated into the crack of bricklaying by a master craftsman. … In order to be moral, to acquire knowledge about what is true and good, a person has to be made into a particular kind of person. … This transformation is like that of making oneself an apprentice to a master of a craft. Through such an apprenticeship we seek to acquire the intelligence and virtues necessary to become skilled practitioners. When the moral life is viewed through the analogy of the craft, we see why we need a teacher to actualize our potential… Of course, the teachers themselves derive their authority from a conception of perfected work that serves as the telos of that craft.

—Stanley Hauerwas, "Discipleship as a Craft, Church as a Disciplined Community"

Hauerwas takes the same kind of language and imagery of the philosophic tradition and here applies it to his understanding of moral life and Christian community. The “moral life,” the life of faith according to Hauerwas, becomes a hierarchical, structural enterprise in how it is conceived and practiced. Just like the tradition of the philosophers, patriarchs, and rulers of the West, in this structural paradigm the Christian community has a clear telos toward perfection directed by those in positions of power and authority, founded on the clear and stable ideals of knowledge and truth. I find it hard not to see this theological frame as running into a brick wall. The paradigms of structuralism and assimilation are inherently imbued with a certain violence, a closedness to the marginalized or different, with a tightly clenched fist around the security of sameness, order, and active subject.

The Other

Standing out from the brick wall, standing against the system of structuralism, we meet a ghostly form of The Other (2), a form of organic, human curvature, juxtaposed with the rigid gridded pattern in the background. It is the other that sounds against the system of structuralism; it is the other that poses the problem, the spoke in the wheel. For it is the well-being, the humanity, and ultimately the life of the other that is at stake in all the systems and structuralism of orienting life and meaning.

The other, that is, God or no matter who, precisely, any singularity whatsoever, as soon as every other is wholly other (tout autre est tout autre). For the most difficult, indeed the impossible, dwells there: there where the other looses his name or is able to change it in order to become no matter what other.

—John Caputo, The Prayers and Tears of Jacques Derrida: Religion without Religion

Here the other is conceived not as a problem to the system, in need of assimilation, but as something wholly other, a singularity, an experience of the impossible—and as thus sharing the same characteristic of transcendence of the “I,” the same alterity, the same opening, as the name of God. Derrida continues, “one should say of no matter what or no matter whom what one says of God.” There is a link between the name of God and the face of the other. This kind of connection is one that resists the ordering structuralism that assimilates the other in violence under the name of divine providence. Rather, the other and the wholly other are deeply interconnected, and are both easily divested of their alterity, closed in, and closed off by the totality of Western philosophic structuralist thought.

An Opening

Feeling the brick walls closing in, the oppressive weight of the structures that in their totality close off the possibility of something new or something other, I look for an opening in the structure. And I find it in a window ajar and a glimpse of sky. For those three squares of light reflected on the window, come from somewhere, outside the structures that fill and close the square window within the frame—challenging the very notion of what would otherwise be an all-encompassing and totalizing structure. It points to something other, something outside the system, to a hope and a longing for something beyond. Searching for openings—reaching for them, creating them, following them—is to practice deconstruction instead of the craft of bricklaying. Deconstruction, however, is not destruction:

Deconstruction is so deeply and abidingly affirmative—of something new, of something coming—that it finally breaks out in a vast and sweeping amen, a great oui, oui—à l’impossible, in a great burst of passion for the impossible.

—John Caputo, The Prayers and Tears of Jacques Derrida: Religion without Religion

This is what deconstruction is all about: it is a hoping, a longing for an opening in the systems and structures that bend toward the violence of closure and assimilation. To challenge the assumptions of philosophic paradigms, to follow the fissures and push their structures to the points of breaking, rending, and opening, is to practice hope. For there would be no hope if everything were already fixed, determinate, and structured. If the story stops at the brick wall, if the closure of the system remains as secure and certain as metaphysics would have it, if the future is nothing but repeating the confines of the sameness in a destruction of difference, then there is a tragic loss at hand. Where is the humanity of the self and the other? If the divine is construed as nothing other than that which orders, maintains, and directs reality, where is promise? Where are hope and faith if everything is certain, deterministic, and based in static knowledge?

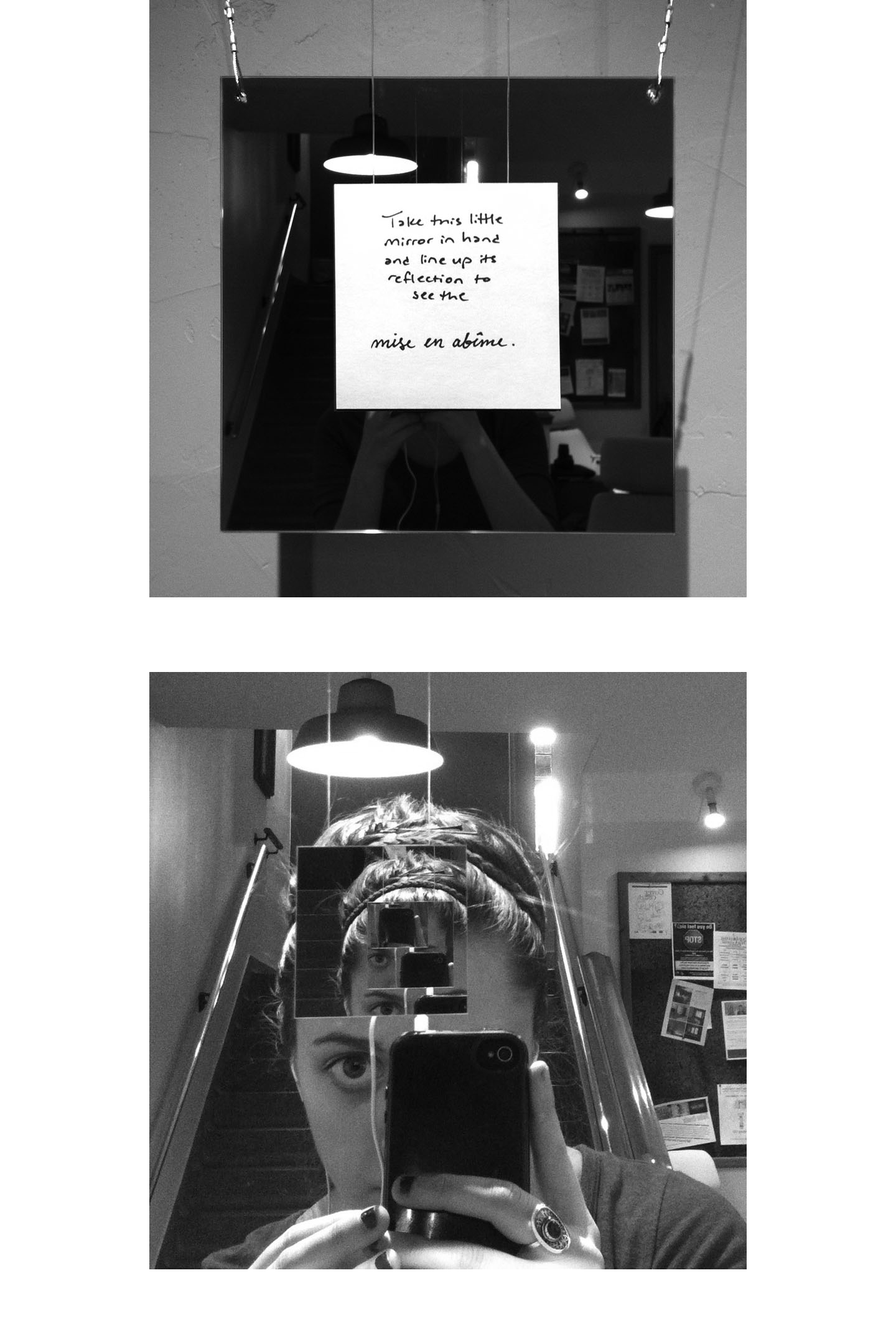

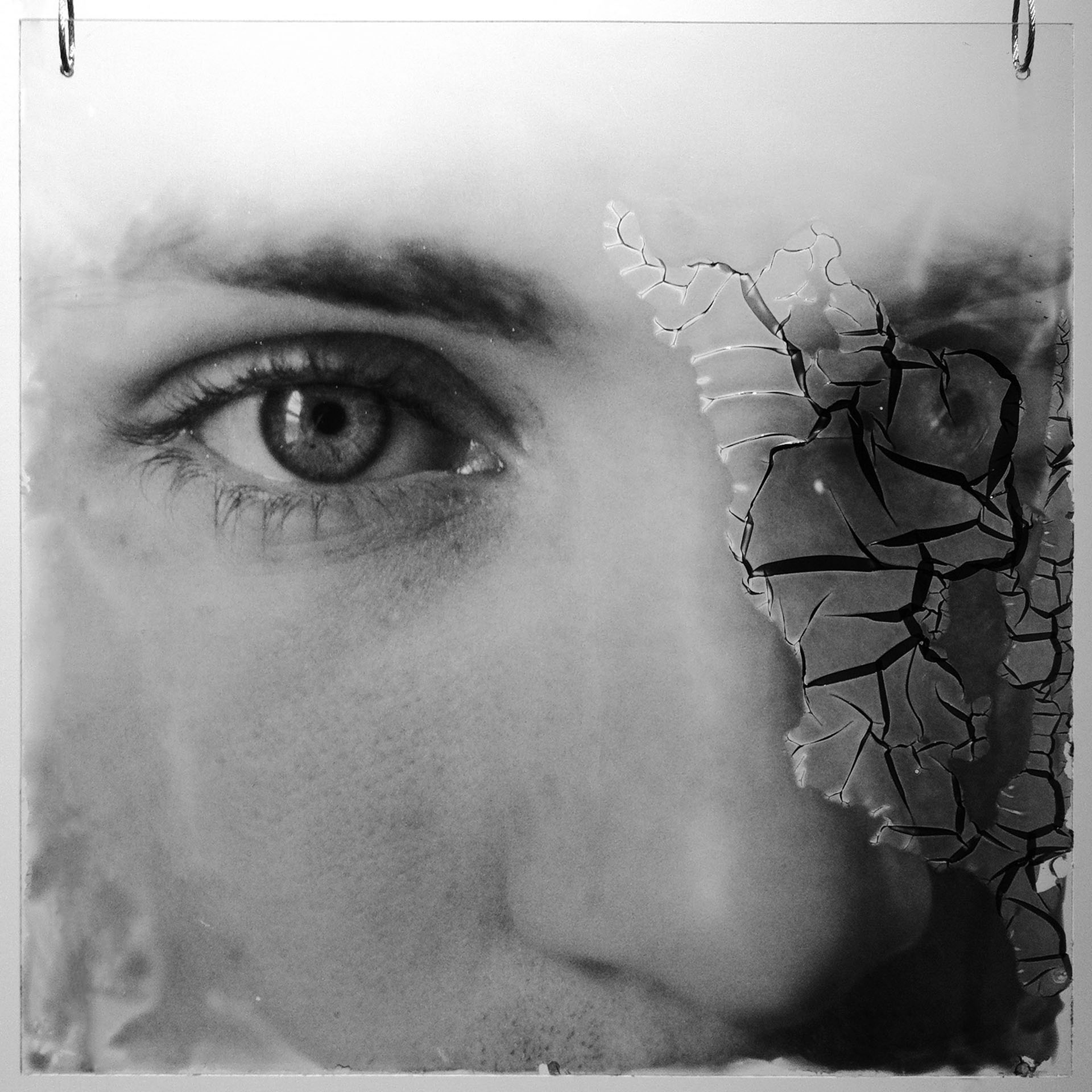

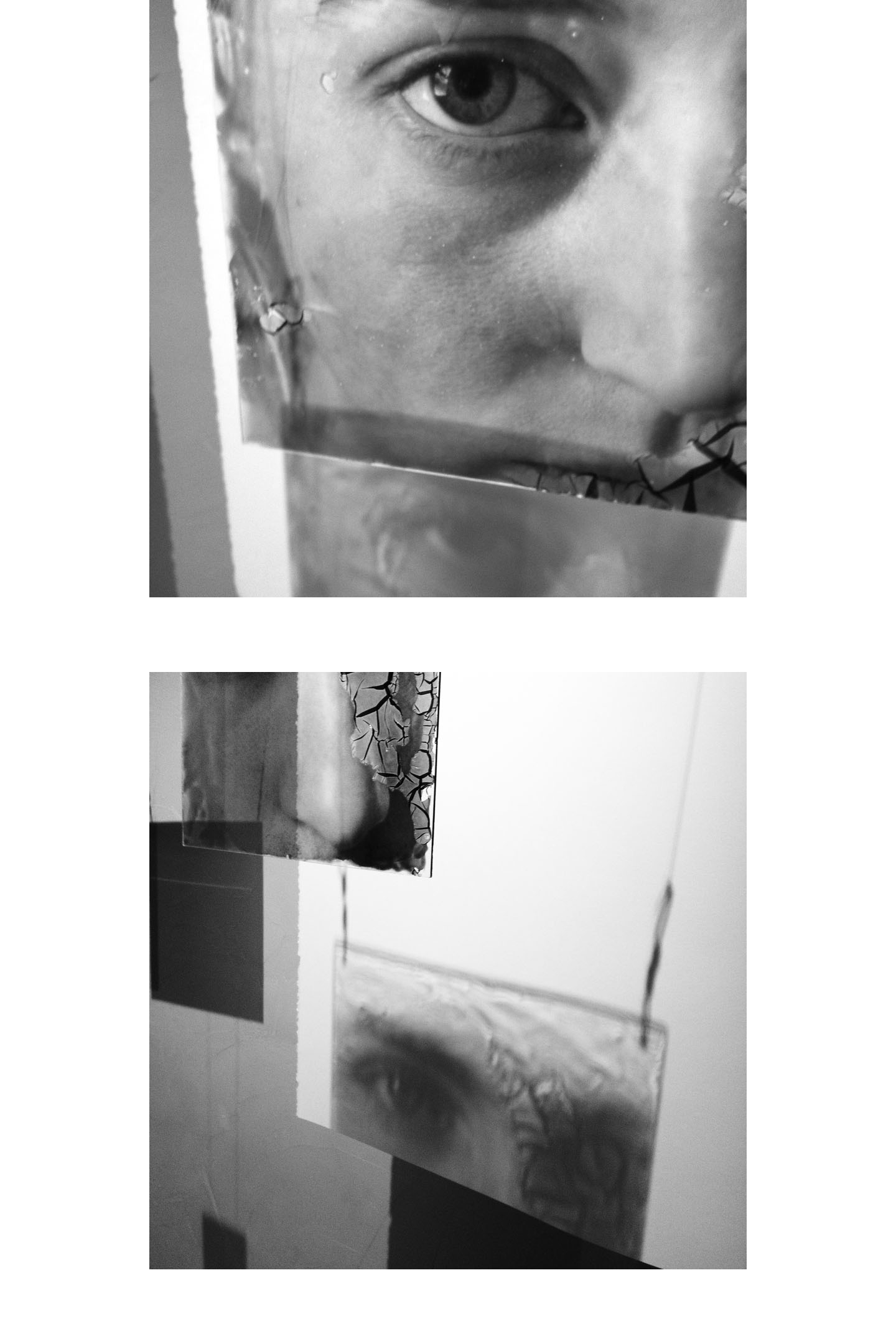

Face to Face: Fragments 1-5 & Mise en abîme

No longer in the plane of straight lines, what had once seemed decidedly fixed becomes an ever receding horizon to be explored. Such a play of images, filled with openness and wavering undecidability, invites a discourse on seeing without seeing, light and blindness, a torn edge, and eyes filling with tears.

Unlike the first three photographs that began this study, the images that appear in Face to Face: Fragments 1-5 and Mise en abîme do not occur within a frame. They are unbounded and in fact, depend on a certain structural openness—on the negative space between the glass and the tear of the paper behind, on the interplay between lights and darkened glass, seen only through a bit of blindness.

Derrida is quick to point out Western assumptions about blindness:

Sin, fault, or error—the fall also means that blindness violates what could be here called Nature. It is an accident that interrupts the regular course of things or transgresses natural laws. It sometimes leads one to think that the affliction affects both Nature and a nature of the will, the will to know [savoir] as the will to see [voir] … Idein, eidos, idea: the whole history, the whole semantics of the European idea, in its Greek genealogy, as we know—as we see—relates seeing to knowing.

You see, the whole way language is formed around seeing, the very place of sight in the popular imagination and discourse of the Western world, is characterized by knowing. Thus, to not see, to hold the condition of blindness, either physically, metaphorically, rhetorically, or allegorically, is assumed to be either unnatural and thus tragic or the willingness of a bad will that chose to close one’s eyes.

Yet the face—the very place of sight—is anything but free from uncertainty and blindness

The face is a shadowy place, a flickering region where we cannot always trust our eyes. And my interest lies not in reducing this ambiguity but in exploiting it. There is a lot of what Derrida calls undecidability and dissemination written all over the face, which is a tricky place, full of ambiguous signals and conflicting messages. We speak of something being true or false “on its face” (super-faciem, sur-face), and that means in an entirely manifest way, with nothing hidden, left behind, concealed. But of course the human face is anything but that. It is, on the contrary, a hall of mirrors, a play of reflections, a place of dissemblance and dissimulation, sometimes a place which we manipulate in order to produce an effect, sometimes a place where the truth gets out of the bag on us against our will. Sometimes our face betrays us, and sometimes we give the lie to others by putting on a convincing face. The human face is anything but simple and unambiguous, anything but just surface. It is streaked with hidden depths and concealed motives.

—John Caputo, Radical Hermeneutics

Speaking of shadows and darkness—the darkness of this darkened glass—let us turn now to speak of cinders:

I hear well, I hear it, for I still have an ear for the flame even if a cinder is silent, as if he burned paper at a distance, with a lens, a concentration of light as a result of seeing in order not to see, writing in the passion of non-knowledge rather than of the secret. I would say, for the protection and illustration of its own sentence, “I” the cinder would say that his (my) writing is not interested in knowledge. The raw cinder, that is more to his taste.

—Jacques Derrida, Cinders

The poetic image of cinders runs completely counter to the radiant beams of illuminating light that come to mind with “Enlightenment” or the Christian equivalent of “Light of the World.” Cinders are still a light, yet one that is dim and smoldering, threatening to fade and disappear at any moment, wavering in instability. Cinders will soon become nothing but ashes. Cinders don’t shed a light of understanding but one of confusion and scattering; their meaning is still there, yet over there, just out of reach, with certitude held under the erasure of the burning light of a fire.

In historic photographic process, there are cinders. Il y a là cindres. In all of the photographs that make up this exhibition, the images are made of cinders—the lingering trace of an event of burning. Unlike digital photography that records the incoming light into computer data organized by pixels, historic process photography depends upon the interaction between light and the physical material called emulsion, a silver-based chemical compound that is “light-sensitive.” When the light hits the emulsion, the interaction is one burning. With respect to the film in the camera, when the shutter opens the places where the bright burns into the emulsion are dark and the spaces of dark shadow that block the light, remain light and transparent on the film—this creates the negative image on the film.

The clear glass here is the site of the cinders, not the stable paper or delineating matte and frame, but rather a transparent, floating image. You can only see the image if you also see through the image, beyond the image. The eye cannot fully stop at the surface; it must waver between the image on the glass and the space beyond. In such an interaction, the image changes, becomes more or less clear, as one walks around it. This sort of print would be a nightmare for Kant, as it is continually being infiltrated and contaminated by the surrounding context on which it entirely depends in order to be seen. It is caught in all the complex webs of meaning that context brings with it, not sheltered in aesthetic purity but recognized as participating in the constructs of meaning that we grasp in the flux of life. They float like ghosts, no longer stable entities but vague outlines that surprise and frighten us with all their uncertainty. They cannot even be seen apart from floating in space—if the glass was right next to the wall, the image would be obscured by its own shadows as the light passes through it. Yet even floating at a distance, the shadows are still there. See? It’s own image disseminates further, casting more shadows, a positive image that acts as a negative through which light continually burns… scattering ashes, lingering cinders carried off into the distance, cast across the walls, bounding faintly along the floor.

Again to show this entry at every moment into the imminence and historicity of the phenomenon, we can say: the epiphany of the face is alive. Its life consists in undoing the form in which every entity, when it enters into immanence, that is, when it exposes itself as a theme, is already dissimulated. The other who manifests himself in the face as it were breaks through his own plastic essence, like someone who opens a window on which his figure is outlined. His presence consists in divesting himself of the form which, however, manifests him. His manifestation is a surplus over the inevitable paralysis of manifestation. This is what the formula “the face speaks” expresses. The manifestation of a face is the first discourse. To speak is before all this way of coming from behind one’s appearance, behind one’s form—an opening in the openness.

—Emmanuel Levinas, “The Trace of the Other”

Such dissemination is juxtaposed with the repetition of reflections in mirrors:

Mise en abîme: this French phrase describes a puzzling visual image in which the image repeats itself infinitely. It is, in fact, the experience of standing between two mirrors, seeing the images play back and forth into an abyss, the abîme. Such an image, while delightfully destablizing, still struggles against the repetition of sameness that carries it off beyond sight. Yet, the notion of face to face, which follows also a repetitive back-and forth dynamic, I envision not as clarity but the openness of otherness that breaks the bounds of confining, repetitive sameness. Turning again to Levinas’ notion of the face of the other, we see that coming face to face invokes a constant play between the interaction of signifiers, of the face’s physical immanence, and the otherness that continues to exceed it.

For now we see in a mirror as in an enigma but then we will see face to face.

—1 Corinthians 13:12 (my translation)

The point is not the identity of the other—be it a homeless blind man or God herself—but that the experience of every other, is one of the wholly other, of the divine. Tout autre est tout autre. Such otherness is manifest alike in the passing glance exchanged with the stranger, in the deep questioning stare of a lover, and in the passionate longing for future that is completely unimaginable. Such interaction, the back and forth seeing and being seen that happens in standing face to face, is so much deeper and complex than an enigma, yet opening and hopeful, filled with longing and desire.

Still, the face is the site/sight of another otherness—that of tears.

How wisely Nature did decree,

With the same eye to weep and see!

That having viewed the object vain,

We might be ready to complain

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Open then, mine eyes, your double sluice,

And practice so your noblest use;

For others too can see, or sleep,

But only human eyes can weep.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Thus let your streams overflow your springs,

Till eyes and tears be the same things.

And each the other’s difference bears;

These weeping eyes, those seeing tears.

—Andrew Marvel, quoted by Derrida in Memoirs of the Blind

Now if tears come to the eyes, if they well up in them, and if they can also veil sight, perhaps they reveal, in the very course of this experience, in the coursing of water, an essence of the eye, of man’s eye, in any case, the eye understood in the anthropo-thological space of the sacred allegory. Deep down, deep down inside, the eye would be destined not to see but to weep. For at the very moment they veil sight, tears would unveil what is proper to the eye… the truth of the eyes, whose whose ultimate destination they would thereby reveal: to have imploration rather than vision in sight, to address prayer, love, joy, or sadness rather than a look or a gaze.

—Jacques Derrida, Memoirs of the Blind

On the verge of tears, I once again draw to the edge, the torn boundary—a tear. For tears welling up in the eyes feel not unlike a tearing open of something inside. The homophone renders a double entendre: tears and tears. It is this tear, this torn edge, does something, in its rending it reveals, disfigures, transforms, upends, and opens to something other. Drawn to this edge, this negative tear creates an opening, the broken boundary between a stable plane and the void beyond. Seeing through the eyes of these transparent faces, is some unchanging soul or stable entity, nor a map of character correlating to the signifiers of the surface of the face, but a tear, an edge and an opening. The very boundaries of the face, its image and form rendered in photographic art, is not the frame but the tear, the open space or void between the glass and the torn paper, the fragmented margins that refuse to enclose. Instead the boundaries are a place of the tear, of a wavering undecidability and openness. An open where not to see. A place of seeing through, seeing beyond, seeing without sight. A place of tears, of impassioned longing, praying, hoping, imploring for the tout autre, the wholly other. Viens! Oui, oui.